machine learning with big data

Imagine doing data entry for months in Excel. Imagine flipping through pages of plant blueprints and instrumentation diagrams on the hunt for instruments with tiny alphanumeric codes. Imagine that, even with your chemical engineering degree, you don’t recognize these codes because they are different for each customer; their descriptions are written in Arabic, Korean, Spanish, or Italian. Imagine your job is to type them—all 10,000 of them before the plant can even run.

Timeline

August 2019 – June 2020

Employer

Honeywell, Atlanta, GA

dreaded data entry

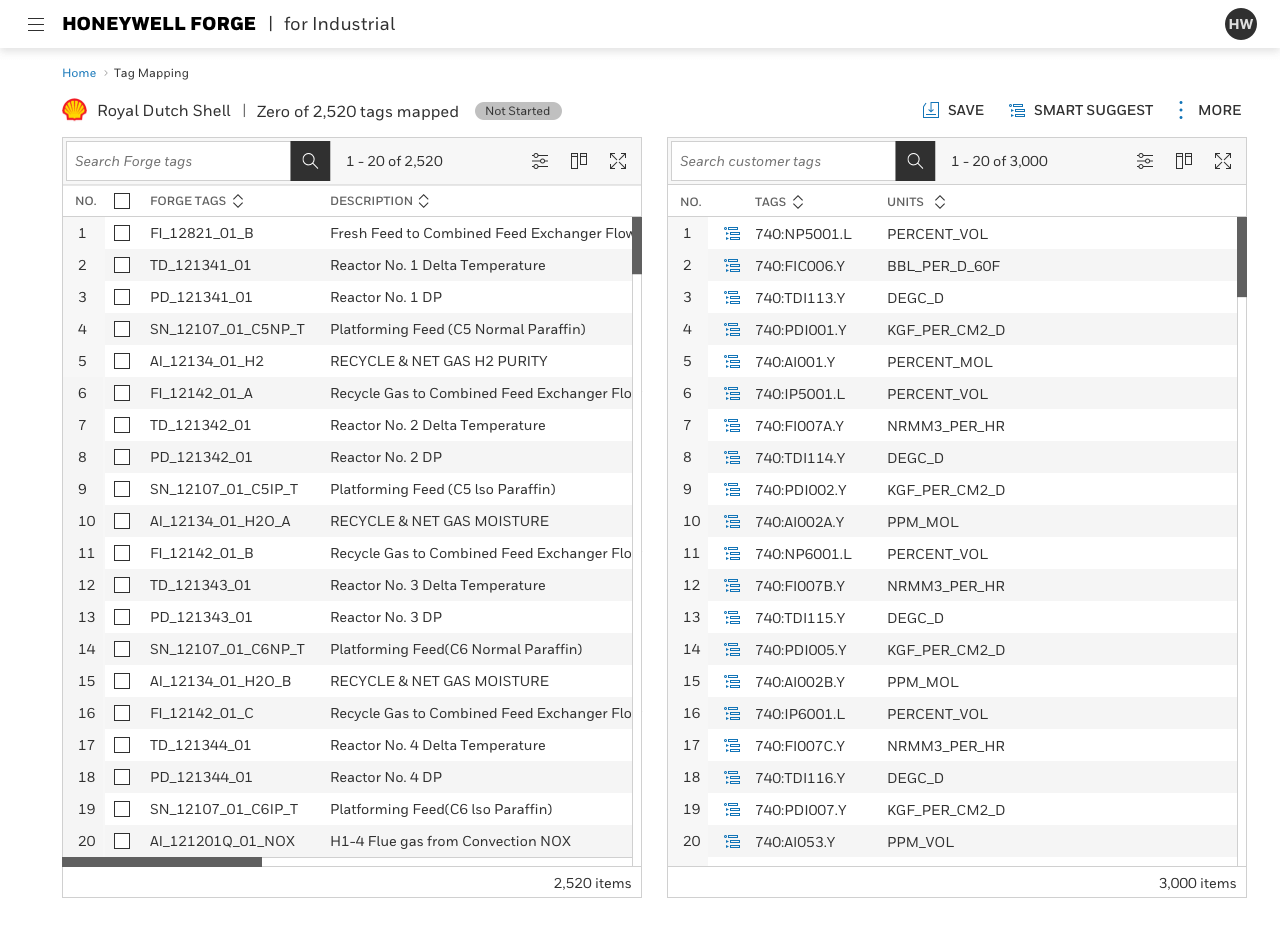

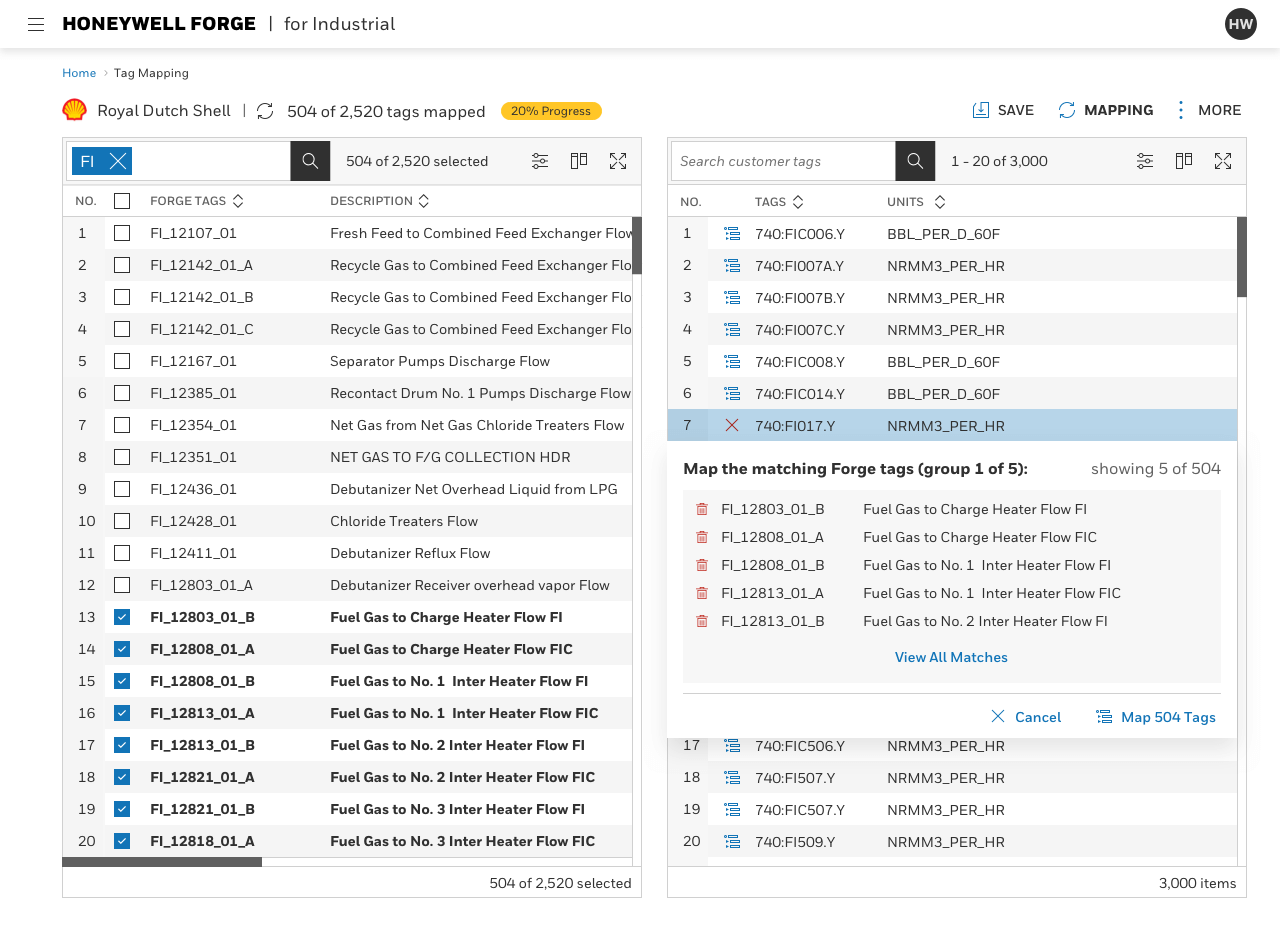

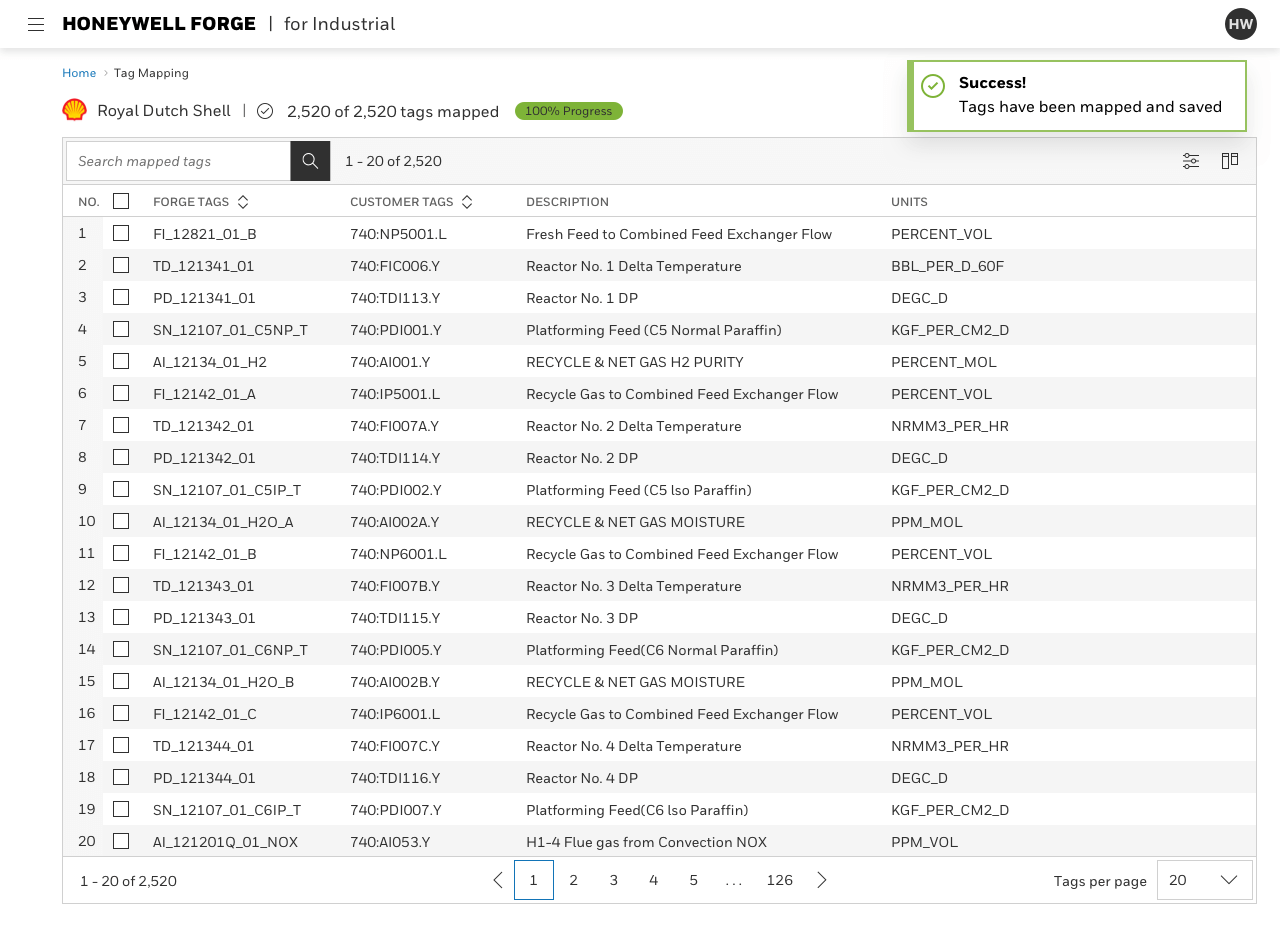

Setting up a plant to send measured data from Honeywell sensors for optimization of petrochemical processes could take up to 6 months. I was lead designer on transforming this Excel-based monthslong struggle into an hourslong task with algorithmic datapoint matching. This machine learning endeavor is called Tag Mapping.

Given a process and instrumentation diagram (P&ID) from a customer, Honeywell's chemical engineers would have to play part translator and part cryptographer. The pictured animated P&ID is from a Korean plant. Each one of those tiny codes matches an instrument that engineers use to run plant processes and manage levels, like temperature and pressure, for manufacturing everything from crude oil to medical-grade plastics.

Please FILL THIS CHRISTMAS SPREADSHEET with coal TO KEEP THE LIGHTS ON

With 1000s upon 1000s of customer datapoints to map to Honeywell tag names, chemical engineers would start with a blank Excel template. In the pictured Excel screenshot, the green columns are dropdowns whereas the red columns require manual entry of the customer's alphanumeric codes, or tag names.

Honeywell’s chemical engineers would have to enter customer tag names found in the P&ID one-by-one, mapping each to its Honeywell counterpart installed at the plant. This would create a digital twin of the entire plant, including its miles of pipes, compressors, heaters, pumps, thermometers, and other equipment, within Honeywell’s database.

Thanks for your six months of data entry. I hope you didn’t enter any typos ;)

Once the Excel templates were filled properly, chemical engineers would then upload them into Honeywell's Model Builder web app. If any tag was mapped incorrecly due to a stray character or typo, it and all of its 100s of connected attributes would not render.

To be frank, this process was awful. It was extremely time-consuming, tedious, and error-prone. Because chemical engineers spent months on this setup process, they had little to no time to lend their optimization expertise to customers. What they were actually hired for, none had the time to do.

As soon as I was tasked with this initiative, I and my design team's research manager interviewed 17 colleagues and users in chemical engineering, product, software development, and data science roles. We received countless demos and process feedback along with walkthroughs of an ideal workflow. Next, we designers conducted workshops with data scientists and developers all over Honeywell worldwide to make this mayhem an automated operation using in-house machine learning.

We came up with a process where chemical engineers would start Tag Mapping in Honeywell's Model Builder web app instead of Excel.

Raw tag names and instrument data from the customer would be uploaded via PDFs of their instrumentation diagrams, then smartly categorized based on the instrument type. Using this method, chemical engineers would just have to confirm smart suggestions from the system. Thanks to the algorithm, tags could be mapped 100s at a time instead of one-by-one. No manual data entry required.

So I'm a mechanical engineer, not a chemical engineer. That fact was never more evident until I joined Honeywell. Translating chem speak into layman's English was a skill I had to master immediately.

challenges

This design initiative saved everyone on the Honeywell and customer sides so much time. It freed up chemical engineers to offer their expertise in saving plants money and eliminating harmful waste.

wins

Big data should be crunched by machines, not people. This project reminded me of why I pivoted to design from engineering, and would make the same decision today.